Sine waves and white noise

Ryoji Ikeda - Audiovisual artist

14 September 2023

by Jacqueline Oskamp

Sound artist Ryoji Ikeda’s artistic quest is driven by the questions ‘what is sound, what is image and what is reality’. His fascination with the smallest unit is a driving force.

From wafer-thin electronic bleeps to impressive interventions in public spaces – over a span of 30 years, Japanese artist Ryoji Ikeda (1966) has built an oeuvre at the interface of art and science, which he exhibits across half the world (Europe, North and South America and Asia). He himself considered his second album +/- (1996) his debut as a sound artist. It is as minimal as minimal can be: from a few electronic tones, a sound universe emerges that is so powerful that there are tutorials on YouTube that explain step by step how to make ‘an Ikeda’ yourself (‘analyze and recreate’). For example, a click sound (the click of a computer mouse) that is sped up and panned left-right across the stereo, already starts to sound like an Ikeda.

cover art of +/-

It says something about the popularity of the Paris-based artist, who is regularly invited to design sound-and-light installations for popular locations. The Radar, a work he has presented in numerous versions in as many locations, took on a spectacular form on the beach of Rio de Janeiro (as part of the Biennale Otras Ideías para o Rio 2012). After sunset, he projected a gigantic grid on the beach, overlaying it with the current position of the stars and planets, with moving beams of light sweeping across it, as in a computer matrix. The ambient music that accompanied this layered visual spectacle subtly blended with the sound of the surf. It was highly popular with the locals: children ran back and forth across the sand, in and out of the illumination, adults marvelled at the mysterious metamorphosis their surroundings underwent, young and old alike were immersed in the orchestrated spectacle and thus part of the work of art – an important characteristic of Ikeda’s approach.

The Radar - Biennale Otras Ideías para o Rio (2012)

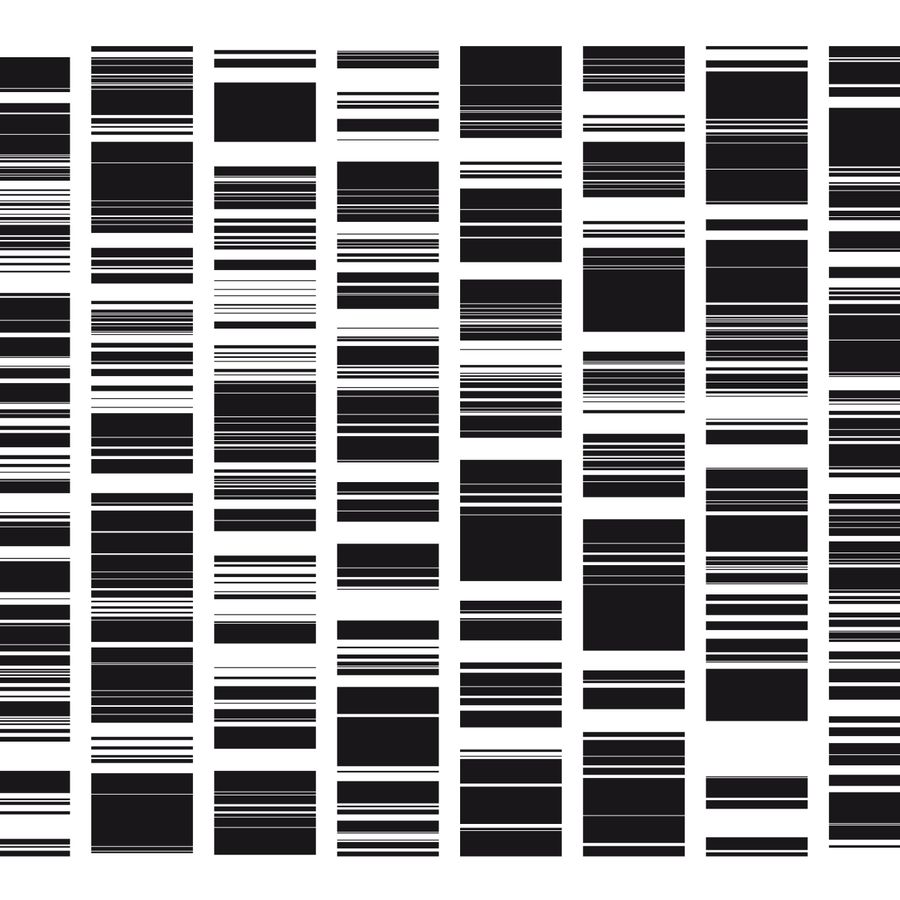

In 2014, Times Square became his canvas – he was given complete freedom to do with it what he wanted. For three minutes, from 11:57 p.m. to midnight, he transformed the neon-drenched Manhattan heart into a stark tapestry of black and white. Over the years, he developed graphic black-and-white patterns in countless variations that rapidly morph into each other: piano keys, crosswalks, barcodes, chessboards, whatever you want to see in them. This time, he let them hopscotch between the skyscrapers, supported by a refined soundscape; a dizzying spectacle. test pattern (2014)

test pattern (2014)

Of a more recent date is Ikeda’s largest exhibition so far. In September 2021, he exhibited 12 works at The Strand in London for over two months. The visitors to this industrial art complex are used to sensory experiences, but after experiencing Ikeda’s audiovisual labyrinth, ‘your eyes can hear and your nose can see’, according to a journalist from The Wallpaper. Even the seasoned reviewer from The Guardian was left discombobulated after visiting the exhibition: ‘To infinity and beyond: The spectacular sensory overload of Ryoji Ikeda’s art’, the headline of her article read.

Ikeda’s work is known all over the world, but he himself remains a mystery. In over a quarter of a century, he has only given a handful of interviews; on the one rare photo of him that circulates, he hides behind a hat and sunglasses; only on YouTube, where many compilations of his work can be found, he occasionally gives a brief explanation. This shyness is not an attempt at mystification. Ikeda has a crystal-clear view of what drives him, as is evident from the few interviews that did appear in print, in which he talks remarkably concretely and coherently about his own development.

For an artist, the work of art is an endpoint; for the viewer it is a starting point

As the spiritual father of a work of art, he does not want to influence the interpretation of the viewer. After all, for an artist, the work of art is an endpoint, while for the viewer it is a starting point. ‘Viewing a work of art should be a kaleidoscopic experience, a beginning without end that invites from different angles and directions’, Ikeda said in a conversation with critic Akira Asada, which was printed in the catalogue for a retrospective exhibition at Eye (2018) in Amsterdam.

Catalogue cover exhibition Rioji Ikeda in Eye Film Museum (2018)

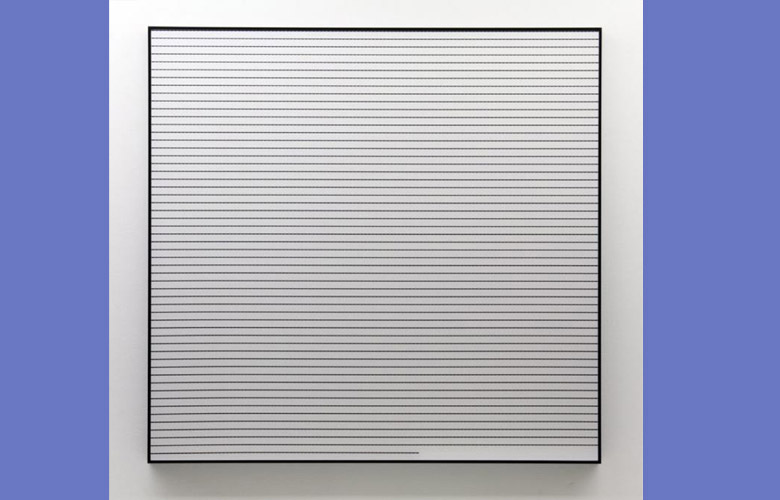

Ikeda has been a familiar face in the Netherlands for quite some time. He participated in festivals such as Impakt, Rewire, STRP, Urban Explorer, Gogbot, and Todays Art. He exhibited in the Vleeshal and gave concerts in Paradiso, Effenaar and Kikker, and more recently in the Muziekgebouw in Amsterdam. Around 2000, he was a regular at Steim, the Amsterdam studio for live electronic music, where he collaborated with kindred spirit Carsten Nicolai (Alva Noto), like Ikeda a pioneer in the audiovisual arts. On YouTube, you can find snippets of Ikeda playing the famous cracklebox of the electronic composer Michel Waisvisz, in his characteristically sober style. Despite his powerful visual language, Ikeda considers music to be the driving force behind his work. Yet it was never his intention to become a musician, he told in two substantial interviews included in the catalogue Continuum (2018). Later, he became interested in the Western avant-garde: Stockhausen, Cage, Boulez, Russolo, and Ligeti. John Cage’s conceptual approach to art and music would remain a point of reference. In 2010, as a tribute to Cage, he made 4’33”: a white square with empty strips of celluloid that together have a length of exactly four minutes and 33 seconds.

4'33" (2010)

A turning point in Ikeda’s life was when he joined the alternative (still active) artist collective Dumb Type in Kyoto as a technician and producer. Working with talented artists from different disciplines who, like himself, were critical of Japanese society in the 1980s (‘Everything was plastic... money, money, money...’) helped him to develop his artistic skills and vision. With the rise of the accessible DJ culture, Ikeda took his first steps on the musical path. He mixed bossa nova and tribal music with abstract electronic sounds, and he experimented with glitch, the malfunction or static noises that electronic devices produce, both intentionally or unintentionally.

He was also heavily influenced by the New York scene: at the Sound Factory, he heard sound systems so insanely loud that they literally took his breath away. ‘I felt fear, physical fear.’ Despite this, in his later work he would often test the limits of what is physically bearable. Whether through diaphragm-shaking bass, stroboscopic light that disrupts the brain, or a darkened hall that disables one’s sense of orientation – an experiment during which he himself panicked.

When Ikeda released his first album 1000 Fragments in 1995, he had three heroes: the Bach interpreter Glenn Gould as a master of recording technology, the New York musician John Zorn who excelled in blending different musical genres together, and multi-talent Jim O’Rourke who epitomised the do-it-yourself spirit. But he realized that he, like so many DJs, was in danger of drowning in ‘the ocean of musical possibilities. Ikeda decided to rigorously pursue the other extreme.

The aforementioned LP +/- from 1996 is based exclusively on sine waves and white noise – the most basic sound imaginable, not subject to copyright and representing two extremes: the sine wave is tightly defined, white noise is chaos. Later, Ikeda adds: the sine wave represents reason, the white noise represents feeling, the romance of a continuum. +/- is his signature, an album he still considers ‘timeless’. From this moment on, his artistic quest revolves around reduction. The question ‘what is sound?’ (answer: sine wave and white noise), is followed by ‘what is image?’ (answer: the pixel), and ‘what is reality?’ (answer: data).

These are the principles that inspire a series of works of art – matrix, spectra, data matics, test pattern, time and space, the radar, micro|macro – which he continues to refine and vary, but all of which spring from a single source: his fascination with the smallest unit, which forms the essence of our universe. Working with ‘data’, such as from weather stations, satellites, financial markets, opens up a world of visual possibilities.

In 2014, he is artist-in-residence at CERN in Switzerland. The amounts of data that are swirling around there are so unimaginably large that he becomes imbued with the phenomenon of ‘big data’, which he tries to visualize. ‘Size really matters when it comes to the reality of data’, Ikeda says. ‘It’s no longer about the difference between a Picasso painting and a reproduction of it in a book, but about the difference between the human scale and the astronomical or the subatomic.’ He translates these immense proportions into his audiovisual installations, in which visitors experiences their own insignificance in a gigantic dataflow that reflects our everyday reality and makes infinity tangible.

micro|macro (2018, foto: Zan Wimberley)

His consistent search eventually led him to fundamental mathematics, a world that became an obsession for him. Around 2008, he corresponded with French mathematician Benedict Gross about large abstractions like prime numbers, cardinal numbers and empty sets – they carry a beauty in them that he had not found in art before. To try to grasp infinity, that is the highest goal of mathematicians. Ikeda: ‘The study of infinity, which has developed from set theory to large cardinals, is one of the most intensive intellectual endeavours mankind has ever undertaken, and it has an unlimited charm.’ As an example, Ikeda mentions the 41st Mersenne prime: ‘To me as an artist, that is a sensational discovery, a number akin to a brilliant crystal.’

It is a beauty that he also recognizes in the form and structures of Bach, as well as in the statement of Jorge Luis Borges, who believed that the straight line is the ultimate labyrinth. In the meantime, Ikeda has taken a new step in his desire to get to the heart of the matter: in recent years, he has started writing compositions for acoustic instruments. No more electronics, but solely the materiality of metal, wood, hair and skin as a source of sound. After some smaller pieces for percussion, in 2019 he wrote the successful 100 cymbals for the ensemble Les Percussions de Strasbourg: ten times ten cymbals, arranged in a tight formation and touched, stroked, and struck in every possible way. Beautiful to look at, enchanting to listen to.

100 cymbals (foto Henri Vogt)

Commissioned by the Muziekgebouw, Ikeda is now creating two new works for the string players of Ensemble Modern. What is certain is that it will result in an unorthodox score: long narrow strips of paper like film strips.

This is a translation of the article that appeared in the supplement of the Groene Amsterdammer on 14 September 2023.