Piotr Anderszewski's paradox

November 28, 2023

Text: Eric Schoones

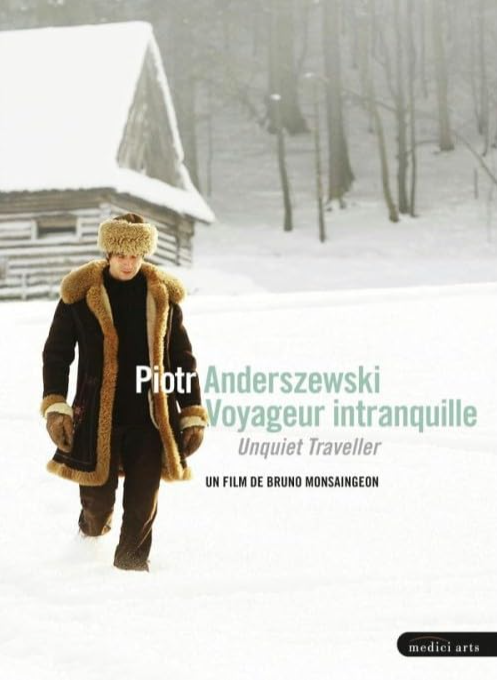

On Jan. 17, Piotr Anderszewski will return to the Muziekgebouw in Amsterdam, where he has been a guest several times. "A great hall with a very appreciative and warm audience," he recalls. Anderszewski is a white raven among pianists, one of the very few who work elusive magic with the sound, as enigmatic as he himself: vulnerable, full of doubts, frank and engaging. And we watched Voyageur intranquille, the film Bruno Monsaingeon made about him in 2008.

You will soon be playing in Amsterdam the First and Sixth Partitas by Bach, some Mazurkas from opus 50 by Karol Szymanowski and the Bagatelles opus 6 by Béla Bartók. You like well-constructed music and that is possibly why you spend a lot of time putting together a program?

Yes, Bartók and Szymanowski both have dance elements, and that works well with the dances from Bach's Partitas. But it is not purely a rational decision; the individual parts of a program must relate to each other. Bagatelles by Bartók is truly a masterpiece, experimental with many folk elements as well.

Szymanowski's very expressive music is known for its complexity.

All music is difficult, it's about telling a story with a thousand connections in a puzzle that has to convince. I haven't played the Partitas for a long time and you can go back to Bach endlessly. My interpretation is still essentially the same, but for example, I now play the Sarabande from the Sixth Partita completely differently. I no longer understand how I used to be able to play it like that.

.png)

Karol Szymanowski (photograph National Digital Archives)

Your selection from the 20 Mazurkas, with very different characters, from introverted to exuberant, also has a nice structure.

I hope so. He wrote them all more or less at the same time. Szymanowski is truly a genius and I only play music I really love. How could it be otherwise?

What was it like working with Bruno Monsaingeon?

Great, he is so passionate about music, he will never betray the music.

A quasi deserted railroad yard, Anderszewski walks with a heavy suitcase between snowy train tracks, he ponders his dilemmas: "I'll never play with orchestra again! So many compromises, from now on only recitals. But that loneliness! No, I will only do recordings, but being able to redo something a hundred times eventually turns against me in impossible choices. No, I'll never go into the studio again, it's so cruel. The ultimate temptation is to stop everything, lie down, listen to my heartbeat, wait for it to stop.' And then the Gigue from the First Partita flashes across the screen, we see the pianist's hands in a vibrant whirlwind of optimism.

Movie poster of Voyageur intranquille

That contradiction reminds me of the paradox you speak of, torn between a quest for the absolute and at the same time possessed of the desire to play, create and destroy. A contradiction that finds its perfect resolution in Mozart's music?

Yes, how Mozart can express the deepest feelings with such lightness, I still cannot understand. He makes me feel alive, and isn't art one big paradox?

In the film, Anderszewski is on tour by train, in his own wagon completely furnished with a Steinway grand piano, something he once did in Poland and Hungary. "I slept on the train to wake up the next morning in a new city. I could walk to the theater, it was ideal. Bruno adopted that for the film. It just wasn't easy to organize, but I would always want to do it that way, to escape all the wasted time with cab, security at airports, hotels...' Anderszewski plays and sings his beloved Zauberflöte, friends come for dinner. Balloons on the wall, wine, schnapps, champagne... 'Food is culture and civilization. I like cuisine where as little has been done with the ingredients as possible, in music it's the other way around.'

He takes a walk with his grandmother who can still remember the history of many decades. She could have been dancing with happiness at his recital. 'If you want to know a city, go to the market, the innards of the city.' We are in Warsaw. 'A whole civilization was massacred and the buildings were systematically blown up by the Soviets and Nazis, what remains is a uniform city for the proletariat.'

Is playing the piano a passion or a profession?

It's great to make a living doing something you love, but any profession can become a problem, and I don't want to play 200 concerts a year. Another paradox: rest is nice, but with lots of concerts, performing becomes easier.

Never considered quitting like Glenn Gould?

He laughs, "I've been thinking that for as long as I've been giving concerts."

Because you are also lazy and a perfectionist at the same time. Another paradox?

I think so yes, all the people who know me well don't believe me when I say I'm lazy. My perfectionism makes recording especially difficult because the result is permanent. And you miss communicating with flesh-and-blood people in the room. Sometimes something happens that you have no control over, then the audience participates in the creation of the music. It's like in life, give and take. In communication, you have to transcend the personal to arrive at something universal. Your personality should not dominate. If I'm less concentrated, I often play better, you need a kind of indifference. And if you want to perform, in a big hall for example, you usually don't succeed. I honestly understand less and less of how it all works.

At a concert in Paris, you say to the audience: I'll play the first piece again, because I wasn't satisfied. It lasts 18 minutes, you are free to go, if you want to go home at all....

These days I rarely do this anymore.

.jpg)

Piotr Anderszewski (photograph Robert Workman - Virgin Classics)

And at your first and last competition, in Leeds, you were 21, you disqualified yourself by not playing your entire program. That says a lot about your character, but you made such an impression that your career was assured anyway.

It was so long ago, it was a different life, anyway it remains a strange way to start a career. But I was ashamed, I was very dissatisfied with my playing. It has to do with self-respect and respect for the audience. My career started in spite of myself.

I found the film very moving, a very personal and vulnerable portrait.

When you allow art to resonate within you, you are vulnerable. Beauty has tremendous power but it can also burn you up.

Because of those universal dimensions we were talking about?

Absolutely, those are very strong emotions. And it's also very difficult to make it a profession. I know so many musicians for whom it has become routine, I won't name names, but then the music is dead. It's a struggle anyway. It is also no problem to play the same program for a year, as long as you can keep the uninhibited spontaneity.

This article was published previously in music magazine de Pianist.