Great art is magic

Kaija Saariaho - HUSH

Finland's Kaija Saariaho composed HUSH in her dying year of 2023, a record of approaching death. Her music is immortal, her mirror is yours. Just listen: everything is exposed.

Makes sense, the Saariaho Festival at the Muziekgebouw. Because the music is so beautiful, that's one thing. And because it gives the opportunity to look back at her oeuvre in the perspective of time. It's more than musicological enthusiasm. With great artists, you want to be able to take stock. Great art is magic. You would want to understand what sucked you in.

Amsterdam will feature works from all periods of Saariaho's life. The highlight - because it is a painfully crushing piece - is the swan song the Netherlands has yet to hear live, the trumpet concerto HUSH from her dying year of 2023, record of impending death. But the unease that resonates there was always there with Saariaho. Wandering around the dreamland of her oeuvre brewing in anxiety and sonic beauty, something stands out: the pieces are like paragraphs of an odyssey. There is a restlessness beyond beauty, a longing for vista, haunted by something heavy for which there are no words. There is no plot. Perhaps HUSH is the explanation. The music is immortal, death is the end. Sounding existence retroactively becomes the composed fear of death. That timely should shine like an eternal light, then it has not been in vain. The music paints an infinite silence with color, movement and light.

-web.jpg)

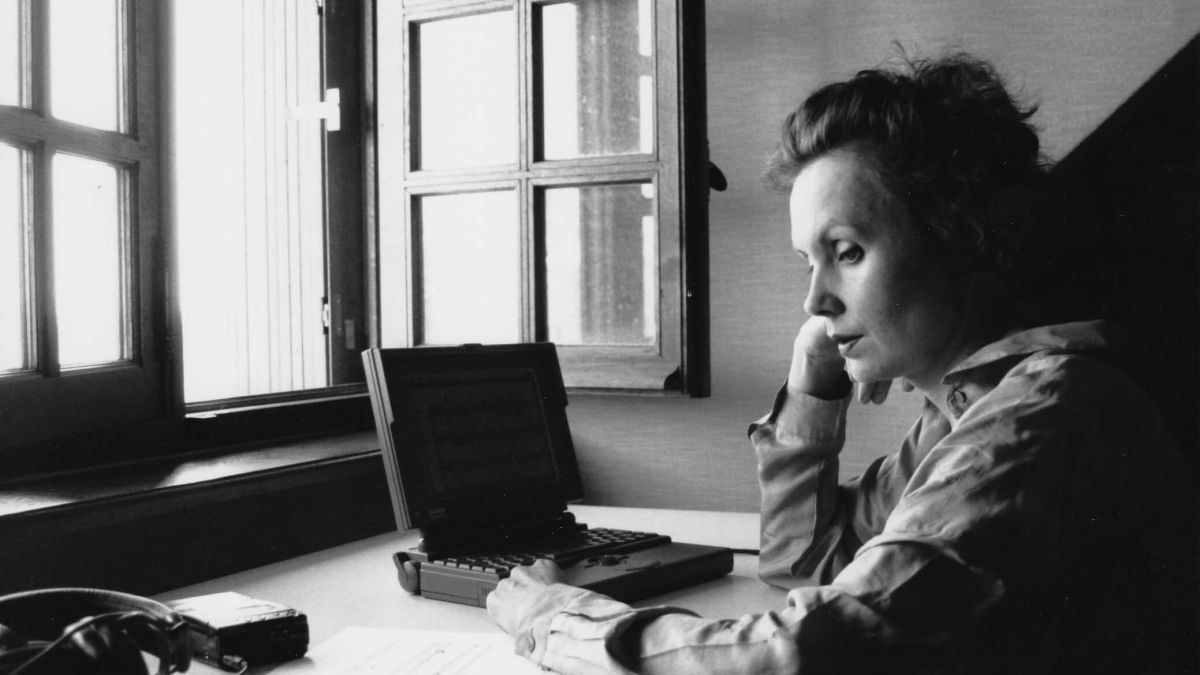

Kaija Saariaho (foto Maarit Kytîharju-Fimic)

Saariaho's titles are already like that. They analyze the tone of voice and the luminosity of the colors in the tones. Changing Light. Laterna Magica. Notes on Light. From the Grammar of Dreams. Château de l'âme. Prospero's Vision. Lumière et pesanteur. Orion. They are about her roots. They come in spirit from a dark Scandinavian country where light is something special and sound is a break with silence. They are born in the dreamer's fantasy world. They are also misleading. They suggest neoclassical prettiness and new age, which the watchful Saariaho is pertinently not. This is not impressionistic loafing. It can erupt with her ecstatically, squeak and creak grumpily, landlily dissatisfied with the artfully raked beauty she is so good at to her own, sometimes palpable annoyance. Simply beautiful is dead, a body without a skeleton. So you hear her sometimes narratively fleeing from that piece of her being.

The dreadful critic’s word "uncomfortable" applies to Saariaho. The music seeks, deflects and diverges, and you feel where it wants to go. From far to further nowhere, to new planets. What comes wants to disappear, what goes does not succumb. Terra Memoria for string quartet from 2006 sets off murmuring. It is a delivery of sadness, carried by a shaky leading rhythm, a lamentation of strings from woefully inarticulate to abrasive and poignant. Saariaho is always serious, but never desolate. What guides her is desire. Darkness always gives birth to light with her. The music wants to shine, translucently. Arcs of Light (1986) for nine players and live electronics is an acoustic arc of light. The wry Solar (1993) for ensemble and electronics would not have been out of place as a soundtrack to the bitterest moments of the masterpiece Interstellar. The light hurts the eyes.

_web.jpg)

Kaija Saariaho (foto Sarah Wijzenbeek)

'What guides Saariaho is desire. Darkness always gives birth to light with her.'

And then the body falters, while the mind continues to haunt more insistently than ever. It is too late, and yet all must pass. Saariaho's swan song HUSH begins as music that must reinvent the wheel. It introduces itself as a limbo, a composed drift in search of the flints, whooping and sliding and scraping but not getting out of place. It widens into macabre continuum from one brilliantly shimmering overall sound with the soloist as a sometimes slurring, jazzed-up bartender at a fictional bar, a macho Siren for a comedic Odysseus. The trumpet represents life with the tenacity of its maker, the unbreakable counterforce. Brave, strong, powerful, energetic he must play, Saariaho prescribes. Then death stomps in. In the second movement Dream of falling, doom arrives with slow-falling, swooping lines of trumpet, screaming drowning in a halo of strings crying along. Part three, What ails you, is cutting docudrama. The trumpet roars, the orchestra pounds with the monotonous rhythm of the mri machines scanning the ailing composer. In the cadenza furioso screams by the soloist, with “quick alterations of playing and shouting” in a directed outburst of despair and rage, followed by an abyssal general pause; then back to that monotonously thumping orchestra, a dismantled Sacre. The soloist seems to be choking. Somewhere a death rattle. The orchestra bleeds from apocalyptic wounds. Again, human groaning and hallucinatory lyricism, double-hearing as double-seeing. Then, over the final bars, the catharsis in the words “bless, Ink the silence,” sung and played by violins and celli. The sound darkens, over the height falls a shadow.

%20LR.jpg)

Verneri Pohjola (foto Teemu Kuusimurto)

Gone. Everything. "When the movement stops," writes Saariaho in her score notes, "we understand that it was the landscape that was moving and not the traveler, and we peek beyond the façade of illusions, into a silence that we have loaded with memories." There is much weight in that. That the traveler was not traveling at all, but from a fixed point saw something much greater moving. The odyssey was an illusion, the search was passive, watching moving images. It is more than the romantic acceptance of the end. It speaks, almost mea culpa, a melancholic verdict on a body of work.

"I was never an astronaut," says Saariaho. "I looked from the earth at the stars. I wasn’t searching. It may have sounded like that. But I sat and beheld something of which I was no more than a tool. I gathered memories and translated into sound what I saw: light and dark." A farewell in music cannot be more cathartic. HUSH is a hard, bitter piece of a doomed honesty. And human, and sweet in the good, grand sense of the word. Below the closing measure is “thank you Anssi”. Anssi is the Finnish cellist Anssi Karttunen, who, like Saariaho, moved to Paris and wrote down Hush's music for the ailing composer when Saariaho was unable to do so. They were closely connected. For him, she wrote the five-movement cello concerto Notes on Light in 2006. Its about light, you could wait for it. Sounding and darkened light, the titles say. Translucent, Secret, On Fire, Eclipse, Heart of Light. It's beautiful. And it fits the time.

Much modern music is fluid, language-less full as the dream, a buzzing totality of acoustic impulses, metaphor of kaleidoscopic reality, cleansed into stream of consciousness and streamlined into artwork. The music of time is the river of history. That is what Saariaho is looking at. From the shore, she discovered. Otherwise you couldn't see the flow. There had to be distance.

.jpg)

Anssi Karttunen (foto Irmeli Jung)

This is how you hear the music of Kaija Saariaho, now that she is dead. She represented time. She sought closeness and found distance. She came from Finland and went to Paris, briefly from silence to chaos, from nature to aesthetics. And she reconciled both, which is also a merit, because art is dramatized reflection on man and his world. She found that synthesis.

Graal théâtre for violin and orchestra (1994), the opening piece of the Saariaho Festival, is one of the works that deservedly made her famous. There is movement, there is tension, but it feels free to take a detour, left or right. There are no binding obligations. The violin solo is immediately ornamental. It doesn’t have to go anywhere. It drifts. The orchestra drifts along with it, with juggler's magic and timpani mischief. There is drama. There are volcanic eruptions. But what remains is the flow of images, an overcast sky seen and captured by a chosen one. It passes by like landscapes from a car. The question of who is moving in relation to what is as current as in the notes for HUSH. The momentum of the second part is temporary. It bangs, it escalates. But the omniverse remains upright like an indestructible bunker.

Saariaho in de jaren 80

How difficult, said Couperus, to judge your own time. But this is it. Time for watching, time for wandering. There is no holy goal, and God is only there for others. The pillars have fallen, the doctrines abolished, everything is open, everything is possible. We are nowhere anymore.

Beethoven's blows disturbed a silence he could still break with music. They imagined new laws, new order, new hope, a utopian marching order. In Stravinsky's Sacre du printemps, you can hear that violence persist over a century later. The modern age is still under construction, the system can still topple - which it would, and how. Now the world itself is the Sacre, normalized cacophony of violent abundance, a deafening reality, a tangle of stimuli from which no human escapes. Murmurs of terraces, the noise of the city, honking cars, pounding streetcars, screaming madmen, screeching brakes, clumsy birds, the pressure of the smartphone, the unintelligible voice of a caller, the violence of death and destruction, of war and inhumanity, of climate murder and moral outrage, too much to handle, too much to solve - and then the silence of a courtyard, just for a moment.

This is an end time. The romantic symphony drove towards a climax for an hour. There was still a way forward. The question is whether the apotheosis can still make a difference. The world is bigger, higher, and more merciless than the cruelest climax. It may be too late for a new Strauss, Mahler, or Bruckner. Music can no longer bend the world like that. So the muse escapes into the magic of wonder, into esoteric capitulation. You hear that in Saariaho. Her mirror is yours. You hear the climate. Humanity is the completed fact that looks into the mirror and asks: who am I, where was I, what should I do? And there is no answer.

This article appeared in the Groene Amsterdammer supplement on 5 September 2024.

Translated by Muziekgebouw aan ‘t IJ.