Kaija Saariaho

Exhibition / full texts

Kaija Saariaho – one of the most influential and innovative contemporary composers – has an unparalleled ability to bridge the realms of sound, silence, and emotion. This exhibition is an invitation into her world of auditory experimentation, where the boundaries between nature, technology, and the human spirit dissolve. Known for her intricate use of soundscapes, Saariaho’s works explore texture, spatial relationships, and the structural complexity of acoustic environments.

“I’m someone who has always lived deeply through my feelings, someone with great sensitivity and an inner imagination – especially for music. I’m a composer with a lot of technique and experience, but I feel very humble because I am not a musician or a performer; sometimes, I’m really amazed by the music that’s created from within me… In the end, it’s all very misterioso.”

Saariaho’s music, which often integrates electronic elements with traditional orchestration, defies easy categorization. Drawing inspiration from the complexities of the natural world – whether the shimmering surface of a lake or the depths of a distant forest – her work resonates with an ethereal quality, evoking both the fragility and the force of the elements. Her keen sense of space and sound immerses listeners in a profoundly intimate sonic experience.

This exhibition goes beyond the musical score, offering an exploration of Saariaho’s creative processes, her pioneering techniques, and the multifaceted dimensions of her artistic vision. Through a combination of music, manuscripts, videos, and interviews, experience how Saariaho orchestrates not just sound, but the very emotions and experiences that make us human.

As you wander through Kaija Saariaho’s journey and words, you will encounter a vibrant interplay of sight and sound – an exploration of the invisible threads that bind us to the world around us, and a celebration of Kaija Saariaho’s lasting impact on both music and the broader artistic landscape.

Welcome to a world where sound becomes a gateway to the profound and mysterious – the delicate balance between the known and the unknown within the immersive universe of Kaija Saariaho.

The Muziekgebouw pays tribute to Kaija Saariaho with the Saariaho Festival. A unique opportunity to get to know this “other-worldly music of a dreamlike quality” (NRC). The four-day Saariaho Festival, co-curated by Oscar Zepeda Arias (Wise Music Group) and Fedor Teunisse (Asko|Schönberg) is the best crash course to fall in love with her work. Study for Life, Saariaho’s very first stage work, will receive its Dutch premiere in June 2025 at the Muziekgebouw. The work will be staged by visionary choreographer, Tero Saarinen, performed by Asko|Schönberg and Tero Saarinen Dance Company.

We would like to thank the Estate of Kaija Saariaho, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Opéra de Paris, BBVA Foundation, Medici.tv, Nayeli Zepeda, Raija Malka, and Jean-Baptiste Barrière for their contribution to this exhibition.

On this page, you will find more information about the manuscripts and a selection of Kaija Saariaho’s interviews

Raija Malka’s gouache work with Kaija Saariaho’s scores are part of their common multisensory work, Blick, presented at Amos Rex Museum, Helsinki, 2021

Kaija Saariaho’s manuscripts have been provided by Paul Sacher Stiftung

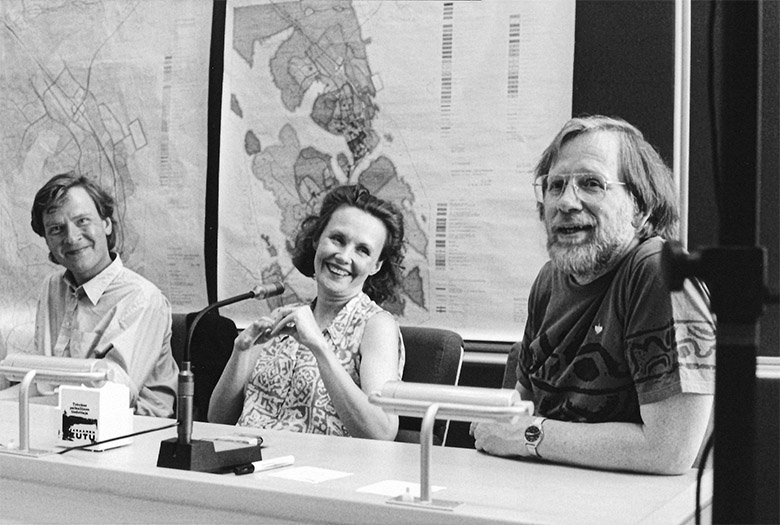

Devising Sincere Conditions

Magnus Lindberg, Kaija Saariaho and Paavo Heininen, Viitasaari, Finland

Who are you, Kaija Saariaho?

That’s a very difficult question… I’m someone who has always lived deeply through my feelings, someone with great sensitivity and an inner imagination – especially for music. I’m a composer with a lot of technique and experience, but I feel very humble because I am not a musician or a performer; sometimes, I’m really amazed by the music that’s created from within me… In the end, it’s all very misterioso.

A composition day

I start composing in the morning and I do not make many breaks. I make a break to have a little lunch and then I continue to compose. I force myself to be in front of my work in the mornings. Sometimes I am very eager to do that, sometimes I am not, but even if I am not, I try to get myself going. As I described, the initial resistance often happens but then you warm up and you are able to continue your work. However, this does not always happen, but one always has to try. So basically, I try to keep myself working.

I have had different periods in my life. When I was young, sometimes I did not even know what weekday we were living in, as I was just working all the time. Then when I got children, for about twenty years of my life I had to adjust myself to their schedules. Here in France the schooldays are quite long, so I divided my life between composition and the role of a mother. Now when they are adults, I am back to a more total way of living in my music. There is nothing special, I just need to have a lot of time and patience and continue to compose.

Composing, a serious responsability

Music is undoubtedly communication. I am convinced, from experiences many times repeated, that anybody, including people who are not musically trained, can enjoy sophisticated music, as long as it is artistically coherent and sincere, and that the presentation conditions are appropriated.

I don’t have interest for music that is arbitrary complex for the sake of complexity, nor do I have respect for music that attempts to seduce people with empty recipes, whether historical or fashionable. There is a populist discourse to consider contemporary music elitist. Of course we can have different tastes, and not everyone need to enjoy the same music. But often one can see, behind these declarations, misunderstanding, reactionary limitations or simply mental laziness, typical in our consumer’s society. This laziness doesn’t concern only music – people are drugged by global entertainment.

Composing and presenting music to an audience is today an important responsibility. The ones who take that path should have an inner necessity for it, and be driven by the idea of having something to communicate, even if this is not at the end any guarantee of musical quality. In the best case the listeners have a curiosity to respect that “gift” proposed to them, and try to listen and hear, as much as possible without preconceptions, what today’s composers and performers have to say

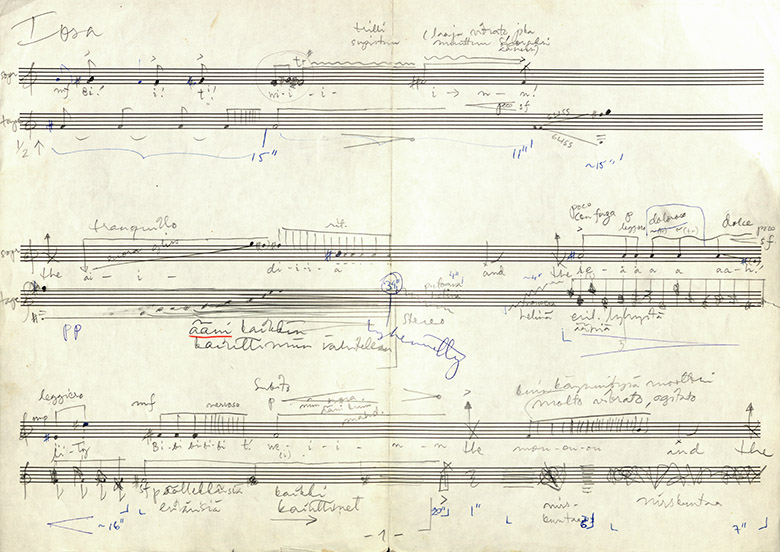

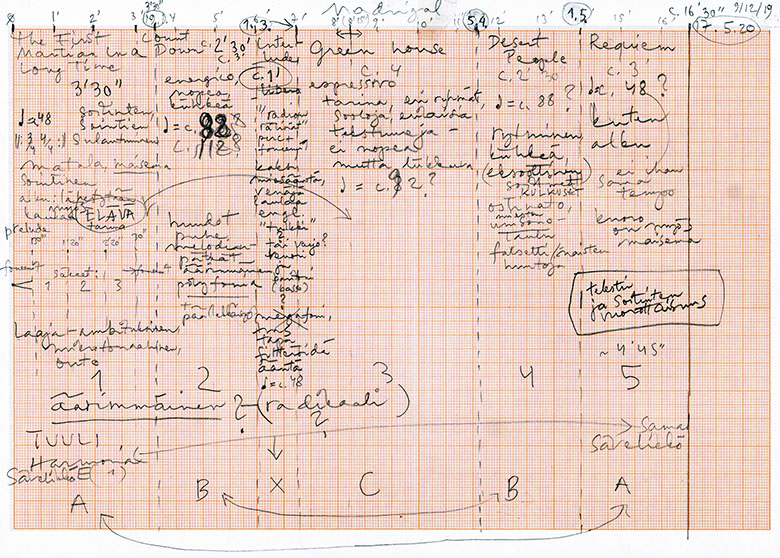

Sketch for Study for Life, Kaija Saariaho Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel

Study for Life – for soprano, tape and lights – is Kaija Saariaho’s first stage work. It will receive its Dutch premiere on 24 June 2025 at the Muziekgebouw as part of the Holland Festival. It will be choreographed by visionary choreographer Tero Saarinen and performed by Raquel Camarinha, Asko|Schönberg and Tero Saarinen Company.

“Study of Life is a twine of glass and white light. It sometimes becomes entangled around the stem – the vocal part – sometimes pushes out new shoots, which prevent the stem from being seem. Light is silent glass, a living image with the parameter of time; scratching glass, tinkling, breaking of glass are sounds of light. “… I could not Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither Living nor dead, and I knew nothing, Looking into the heart of light, the silence. …””

Unraveling the Secrets of Sound

Kaija Saariaho and Jean-Baptiste Barrière mixing at Radio France Studio 104

Kaija Saariaho and Jean-Baptiste Barrière mixing at Radio France Studio 104

Dreaming music

Yeah, it became a kind of an anecdote, because my mother told me that in the evenings, I asked her to «turn the pillow off», because (chuckles) the music was… I was imagining the music came from the pillow and I could not sleep, so I was imagining it, yes… I think I have been always imagining music, but how it was when I was a child, I do not know.

Analyzing sound

I started working with analog electronics already during my studies in Finland in the mid-seventies and created then my piece Study for Life for soprano and electronics. I continued studio work during my studies in Freiburg, and some years later, at the beginning of the eighties, I started studying and working at IRCAM, to learn about the new musical possibilities that became accessible with computers. I analyzed sounds with the tools emerging from scientific research about signal processing, and developed techniques of computer-assisted composition with the help of researchers in artificial intelligence.

This experience and my new knowledge influenced my approach to composition and writing for orchestra. I also studied then psychoacoustic and music cognition and worked with the researcher Stephen McAdams, and learned to understand more about our perception, something that was very important for my future work concerning musical form.

Spectralism influences

After my studies, that had been technically oriented to different historical and serial composition principles, I was looking for solutions to create more dynamic and audibly comprehensive ways to create harmony. In Darmstadt, I had learned to know the music and work of Gérard Grisey and Tristan Murail, who both had different ways to create harmony based on the organization of musical spectra.

Their work encouraged me to find my own way to deduce harmonic structures from computer sound analyses, focusing on the perception of complex timbres produced by various modes of playing musical instruments, in particular flute and cello. I used these analysis materials, more intuitively and freely than Gérard and Tristan did, at least in their early works, and combined them with technical ideas derivated from serial thinking for the organization of my pitch material and other musical parameters.

Blending the tools of sound analysis with my own compositional techniques allowed me to find consistent ways to use microtonality and understand the acoustics and psychoacoustic of sounds behavior. And that has been important for all my composition until today.

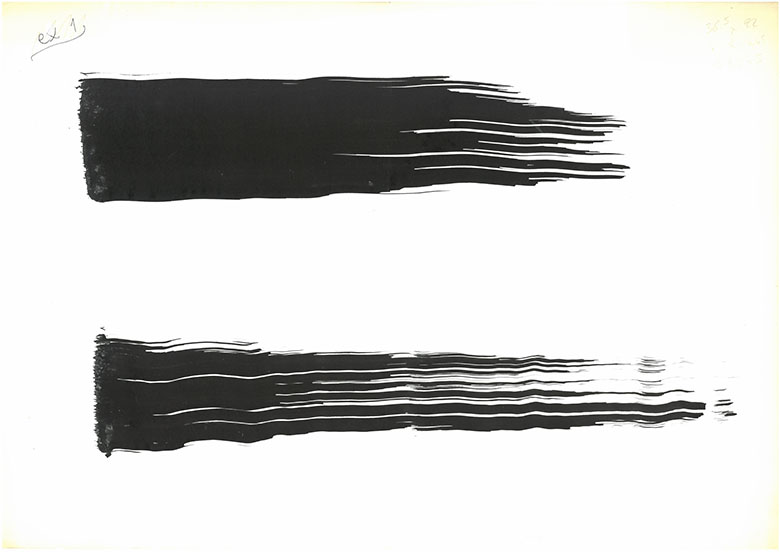

Drawing of Verblendungen, Kaija Saariaho Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel

On several occasions, Kaija Saariaho would make drawings before sketching a new work. This drawing represents her inspiration for composing Verblendungen (1984).

Verblendungen (video)

The tape part has been worked out with GRM's digital tools for manipulating and transforming concrete sound material. The basic material for the tape consists of two violin sounds, a sforzato stroke and a pizzicato. From these two sounds I have built a quasi-string orchestra with a very wide pitch range. The timbres on the tape are very homogeneous because of this single reference spectrum.

The total plan for the use of timbre in the piece is based on the idea that the orchestra and the tape are moving in opposite directions with respect to the tone-noise axis. The piece starts with a thick orchestral tutti, which is first hidden and then shaded by the noise on the tape. During the piece the orchestral colouring is transformed into instrumental noises, which, before withering away, shade the quasi-string orchestra on the tape. The orchestra is built to have a heterogeneous nature to contrast with the even colours on the tape. In spite of their different, sometimes opposite materials, the orchestra and the tape should build a common, inseparable sound world.

When composing the piece an important factor has been the relation of the surface structure and deeper musical and formal structures. In my network of connections between different parameters I am searching for intersections not only vertically and horizontally on the time axis, but also in the direction of depth, as if the sounds were organised in thin layers in three dimensional perspective, starting from dry, grainy sounds in front and moving towards smooth, more resonant ones.

Dazzling, different surfaces, tissues, textures. Weights, gravity. To be blinded. Interpolations. Reflections. Death. The sum of independent worlds. Shading, refracting the colour.

The Unseen

Kaija Saariaho and Esa-Pekka Salonen Reading Adriana Mater, 2006 ©Peter Oftedal

Material and form

From the very beginning, my work has sought to unify material and form. I don’t know why, but I feel like I have to reinvent the form for each new piece. The idea of taking a predefined form and saying, “Okay, let’s write a sonata or compose something according to a classical, predefined form”—it’s just not possible with my music. It can’t survive like that; it would be dead before it was even born! Every piece of music must live its own life because each one is utterly its own. Of course, from one work to another, I might come up with similar solutions in form, given that it’s my style. But I either use them consciously, or sometimes I go against my intuition, because I feel like you have to open up the possibilities, try new things. But to come back to material and form, once again it’s like the five senses—for me, there’s a back-and-forth between thought and intuition when composing, which makes it impossible to separate the two.

Influences

I am sure there have been enormous influences. All the influences, you react to them inside yourself, and then they become a part of your subconsciousness. So only afterward they come from me… but there are many influences, but we are not aware of them, really.

Electronics, a world to explore

Electronics, despite the trivialization of certain types of tools through commercial software, still offers immense territories to be explored, particularly in the field of sound synthesis, for example with physical modelling techniques. I would be very curious to see more efforts in this field, but it requires a lot of work, few composers dare to devote themselves to it. It is a demanding but exciting field, and it is a pity that too often the increasingly difficult conditions of production do not allow for the time to go into it as deeply as it deserves.

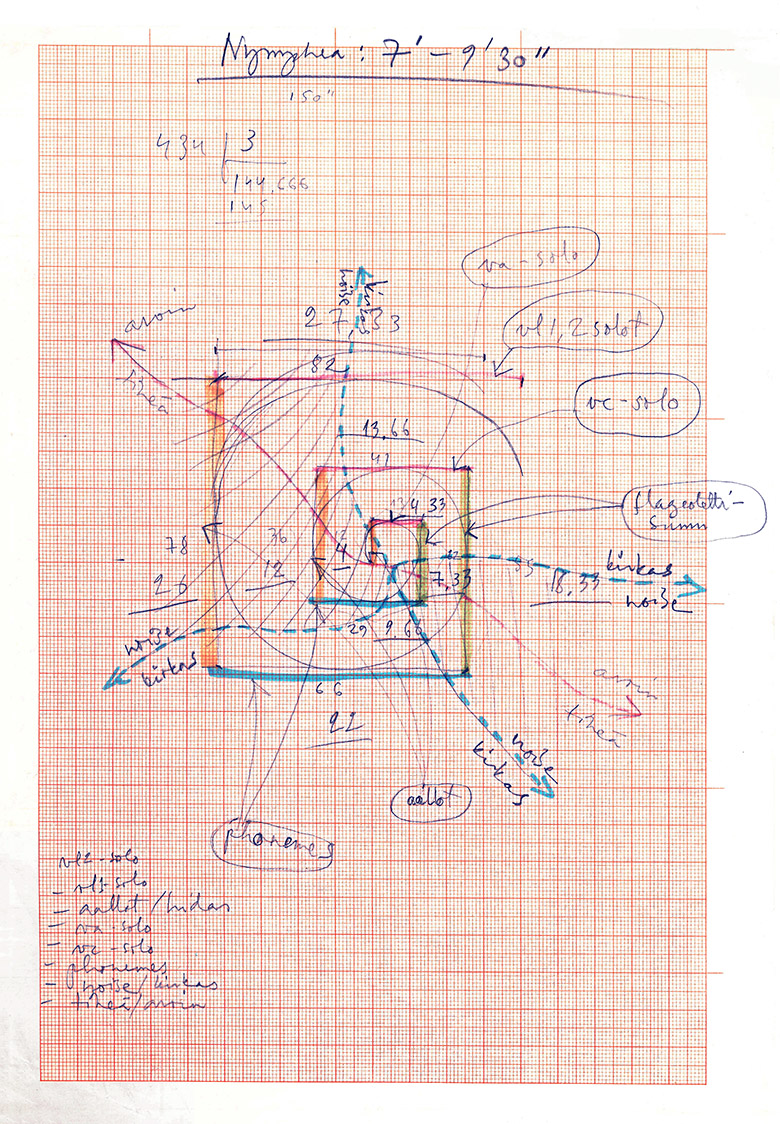

Sketch for Nymphéa, Kaija Saariaho Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel

Nymphéa (audio)

In Nymphéa (Water lily, 1987) for string quartet and electronics, my aim was to broaden the colours of string instruments and create music by contrasting limpid, delicate textures and violent, shattering masses of sound.

The basis of the harmonic structure is provided by cello sounds that I analysed with the computer, through the use of some personal computer programs. The musical material is going through rhythmic and melodic transformations as the motifs are gradually converted from a trill into arpeggios, or unisono rhythms into multilayered micropolyphony. The electronic component of the piece consists of live transformations of the string quartet's sounds in the concert.

Some images that evolved in my mind while composing: the symmetric structure of a water lily, yielding as it floats on the water, transforming. Different interpretations of the same image in different dimensions; a one-dimensional surface with its colours, shapes, and, on the other hand, different materials that can be sensed, forms, dimensions, a white water lily feeding from the underwater mud.

A poem by Arseny Tarkovsky - the cineast Andrei Tarkovsky's father - also became a part of the sonic material during the compostion. It appears gradually, first in separate phonems whispered by players, adding thus a vocal color to the palette of string sounds:

Now Summer is gone

And might never have been.

In the sunshine it's warm,

But there has to be more.

It all came to pass,

All fell into my hands

Like a five-petalled leaf,

But there has to be more.

Nothing evil was lost,

Nothing good was in vain,

All ablaze with clear light

But there has to be more.

Life gathered me up

Safe under it's wing,

My luck always held,

But there has to be more.

Not a leaf was burned up

Not a twig ever snapped

Clean as glass is the day

But there has to be more.

(Translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair)

Kaija Saariaho

Breathing Life into every Word

Peter Sellars, Kaija Saariaho and Amin Maalouf, Salzburg, 1999

Peter Sellars, Kaija Saariaho and Amin Maalouf, Salzburg, 1999

The vocal universe

I have such an affinity for the human voice—and a personal predilection for texts! Everything I just said about music can be found in voice, and in an extreme way. In a sense, it’s the richest form of expression because the instrument is inside a human being and there are many things that cannot be falsified when using your voice. Whether or not a work for voice originates from a text, it’s necessarily a different mode of communication than instrumental music. Of course, using a text adds another layer of richness and meaning. I really love using voice, but it was difficult for me to write for it at first, probably because the historical context was difficult. I’ve always loved Berio, for instance, and what he did with voice, but I don’t like music that imitates Berio—and at some point, it felt as though you could only write for voice in that way, you had to write that way. So, it took time for me to find a certain freedom and my own way of writing for voice—and to accept it.

Language in music

Every language is different. I think my pieces are written in the languages that surround me. When I lived in Germany, I automatically gravitated toward German texts. during my stay in New York, naturally I used texts written in English. When a language is spoken around me, I think I’m influenced—maybe subconsciously—by that environment’s particular sound. What I’m sure of is that each language encourages me to think about the orchestration, the different colors. But I think I’m going to stop writing in French. I’ve already written too much with it. I have to mix things up.

Coming back to the origin of choral art

The idea was to return to the origin of choral art, to the madrigal of the Renaissance, which is also the origin of opera, an opera chrysalis with open potential. But by assigning to this first collective expression an object that is contemporary to us: our collective destiny as we can envisage it today on our planet, an us that is capable of thinking itself in the dimensions of the human species. Reconnaissance is intended to be a "science fiction madrigal". The fable is that, as a collective subject, we set out to attack the planet Mars, asking ourselves what we want to do with our Earth: and Mars, this planet once covered by water and now deserted, stands before us like those Renaissance skeletons that tell us: I was what you are, you will be what I am.

Sketch for Reconnaissance, Kaija Saariaho Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel

Sketch for Reconnaissance, Kaija Saariaho Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel

Reconnaissance (audio)

The word ‘reconnaissance’ contains two contradictory ideas: the English meaning of heroic military exploration of the unknown, immediately refuted by the French meaning which is the re-discovery of what we already knew, perhaps our own eerie mirror image. The high-definition pictures we now have of planet Mars’s arid landscapes, once covered with rivers and oceans that maybe were home to life, bring to mind the same contradictory impression, which must also have been the same kind of metaphysical contemplation the 15th century audience experienced when listening to the apocalyptic imagery of the Franco-Flemish School’s madrigals.

This comparison is what triggered the idea of a ’science-fiction madrigal’, associating two genres that share a deep existential affinity. Indeed, choral music also articulates individual voices and collective fate, blurs the lines of who is saying ‘me’ and who is saying ‘we’. These categories are shattered in our age, when for the first time we are drawn to reflect, beyond our mapped identities, on what unites us as a species, possibly endowed with a shared future, or perhaps with no future at all.

Through creative solutions that question musically what a chorus can be, Kaija Saariaho’s score treats humankind itself as a character, expressing itself both in unison and in fragmented voices, in opposing groups and in isolated individuals. Kaija's very own brand of futurism doesn’t resort to the expected electronics –despite them being one of her favorite instruments– but strip things down to the raw sound material of human voices and a double-bass and percussions, metal against skin. A ’starry night’ typical of her sound world, were it not lacerated by the violence that took us from the canyons to the stars. “Un popolo di poeti, di artisti, di eroi, di santi, di pensatori, di scienziati, di navigatori, di trasmigratori…” Thus crumble the dreams of grandeur by which we pompously define ourselves collectively.

Aleksi Barrière, 2021

Thinking in Terms of Light

Kaija Saariaho at the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, 2017

Light as an inspiration

I think that’s just how my mind works. I don’t actually try to find metaphors; they come naturally. It’s true that I’m very sensitive to light and that I’m inspired by it. Sometimes I genuinely do think about orchestra in terms of light. When I picture certain orchestrations, I make instant connections with light. I feel like the senses are mixed together, but I’m not interested in analyzing why or how that may be. What matters most is that it works and that it inspires me. At any rate, for a long time, I’ve believed that the senses are not compartmentalized, but are in fact far more connected than we realize.

A connection with nature

I think there is some truth to the connection between nature and Finland. The country’s population is so small and nature’s presence there is so pronounced, it’s impossible to lead the kind of urban life you can in a big capital—even though some people try desperately to pretend that they do. Nature is one thing, but what’s more important is light. Changes in sunlight throughout the year are so drastic that they affect everyone. You can’t escape its influence. And because of this experience—which is so physical, we feel it in our body—we, as individuals, have a very special relationship with nature. We have respect for it, we are aware that it’s something larger than us; further, its influence is part of our broader culture and can be found, for instance, in Finnish epic poems, where nature is truly sacred, which was the case for many early cultures.

For me, its importance comes from the experience of living in the “period of darkness”—there’s a very specific term for this in Finnish: kaamos—all the while retaining hope that the sunlight will start strengthening again until it is fully restored. Springtime is extremely long, and since the earth has been covered in snow for such an extensive period, there’s a kind of rotting—though pleasant—smell, which gradually gives way to spring vegetation. My relationship to nature isn’t about admiring the aesthetics of a sunset; it’s something much more physical that I carry inside me.

Study for Life, a work for soprano, tape and lights

It was a time of Luigi Nono's non-operas and Luciano Berio's anti-operas, I was in the same trend: collages, montages, devices.

Opera was a dusty form that was very far from my concerns. Not only for musical reasons: it was the narrative that bothered me. Stories with good and bad guys, caricatured individuals. My vocation was to compose music made of subtle harmonic transitions, of noises that turn into sounds, of slow metamorphoses, because the world is complex and undecidable. I didn't have the imagination for an opera that could show this, despite my love for vocal expression, which took the form of melodies and arias. My first music theatre work, Study for life (1981), was an abstract work for soprano, tape and lights based on excerpts from the poem The Hollow Men by T.S. Eliot. Aleksi [Barrière] has recently proposed a new production, which is like a dreamlike miniature of the poet's mystical crisis.

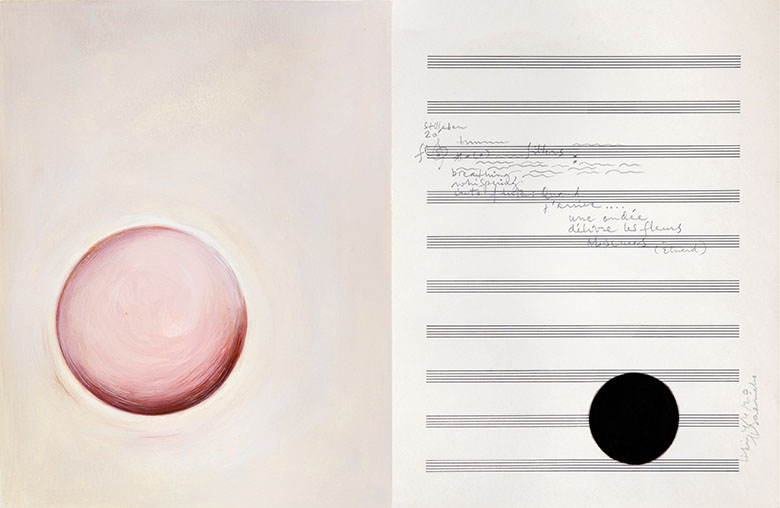

Gouache from the Serie Epilog, 2020 / Raija Malka and Kaija Saariaho ©Raija Malka’s collection

Gouache from the Serie Epilog, 2020 / Raija Malka and Kaija Saariaho ©Raija Malka’s collection

Originally, the Blick exhibition was set to take place in summer 2020. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, a new schedule was set, and the exhibition was postponed by a year. In spring 2020, Raija Malka who had left her home in Lisbon for Helsinki and the construction of the exhibition, remained in Finland to await the next flight back. Kaija Saariaho, a resident of Paris, had also travelled to Helsinki in March. Time passed and nothing happened. The artists started a dialogue: Saariaho sent sheet music to Malka, who then responded with visual comments. This resulted in ten diptychs, two-part works, around the themes of the exhibition. Their shapes and colours, recognisable from Malka’s art, co-exist side-by-side with Saariaho’s musical notes referring to Saariaho’s Stilleben. The collages form the final part of the exhibition, an epilogue of sorts for Blick as a whole.

Raija Malka

Letting things go as they are

Kaija Saariaho and Susanna Mälkki rehearsing Vista, Helsinki, 2021 ©Maarit Kytöharju

Being a composer, rewarding difficulties

Well, I think about it every day (chuckles). It is difficult because it is very solitary work, it is very slow work. This is why I am spending all my life composing. It requires a lot of patience, What is fantastic is, of course, when you have this moment when you suddenly know what to do… and also sometimes, but not often, when you hear your music, and when you feel there are some things that really communicate something — it is a magical thing, it is a great privilege.

Music worldwide situation

The musical scene has been and is still dynamic and lively, despite the culture industry constraints, and the sanitary crisis and its consequences. Besides, there is more freedom artistically and stylistically than ever, at least when people are not obsessed by commercial or personal success. On a broader picture, obviously, the future of music depends directly on the development of humanity; it is connected with the problems of pollution and the destruction of the planet, and, above all, the ever-increasing tendency to evaluate all aspects of human life in economic terms.

We can only hope that we will soon have reached the peak of this insane global materialism, and that there still will be time and a constructive way to reconsider what are the most important values in our society. Sometimes, I feel that this is possible. In spite of globalization today, depending of cultures, there are still major differences in the conditions under which musicians live and in the esteem they have. People have to be conscious of these differences, and fight for the human values they consider really important. Music is an important part of humanity and human expression, and we need to fight to save its diversity.

The mysterious dimension of music

When I compose, my aim is to notate and realize my music as I imagine it. I don’t think of it as mystical and do not try to create a mystery. I am not a religious person. But music has power to open new gates in us, it has a mysterious dimension, which we do not understand intellectually and cannot control. It is like a smell in that sense that it goes directly and deeply to our unconscious mind, before we have time to think about it.

Music can connect with the major themes of human life of which we do not know as much as we would like to, and which we need to approach more with our sensitivity and intuition, as we simply do not have words to explain – I’m thinking here of such basic themes as birth, death and love.

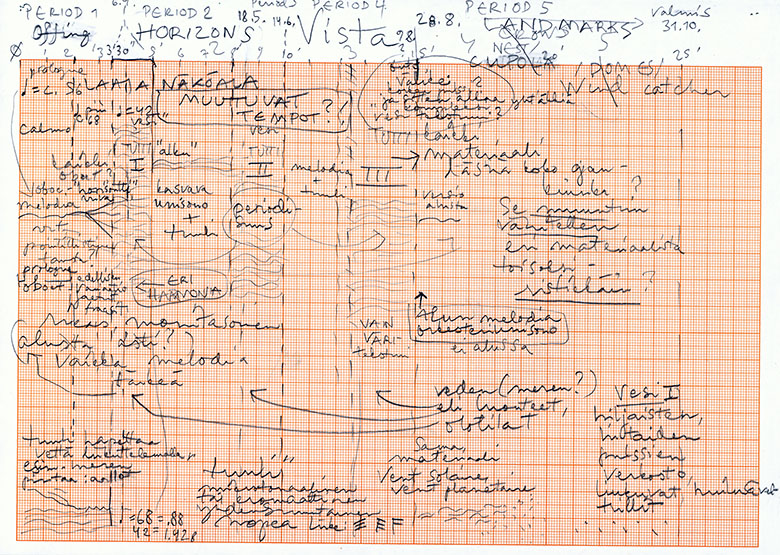

Study for Vista, Kaija Saariaho Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel

Vista (video)

In January 2019 I attended the US premiere performances of my harp concerto Trans with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, played by Xavier de Maistre, and conducted by Susanna Mälkki.

I had completed my latest opera Innocence before Christmas, just a month earlier, and letting my mind get fixed on the ideas that were rousing into my consciousness, planning to get into work after having returned home in Paris. My next piece was to be an orchestra piece for Susanna.

When driving after the last concert from Los Angeles to San Diego for some days, I was filled with joy after beautiful performances and enjoying the scenery on my right during the ride. We stopped every now and then to admire the view, and later I realized that most places were called vistas. As I literally also felt that new music was flowing into my mind and opening new kinds of ideas for the piece, I started calling it simply Vista.

The score has two movements: Horizons and Targets. The excitement of writing for a full orchestra without soloists - after the many years I had used for opera composition - was inspiring, and obvious when hearing the piece. Nevertheless, I also wanted to challenge myself, and deliberately left out some of my signature instruments in orchestral context, namely harp, piano and celesta. I also chose varied colors for the triple wood wind section and wanted to give them more place than usually.

These simple decisions made the composition process challenging, as they forced me to find new ways of expressing myself with orchestra. But after patient digging, I found a fresh sonority, that is more clearly defined without the unifying resonances of harp and piano, and the individual wind instrument lines and textures are prominent. The two movements are using same musical material but are contrasting in their character.

Whereas Horizons is based on lines and abstract textures, Targets is more tense and dramatic, with much physical energy. The formal construction of the piece is based on the different ways of varying the - as such quite reduced - musical material. There are recognizable gestures that go through disparate transformations, and especially in Targets search restlessly new combinations of existence; the several energetic attempts to break out are finally solved into a slow coda section, during which the music returns to the calm confidence of the opening measures.